Chilean activists Veronica De Negri and Marco Echeverría highlighted the lasting trauma from Augusto Pinochet’s regime during a panel at the Elliott School. They discussed the importance of remembering victims, recognizing unresolved human rights violations, and the need for public memorials. The speakers shared personal stories emphasizing the responsibility to confront the past to prevent future atrocities.

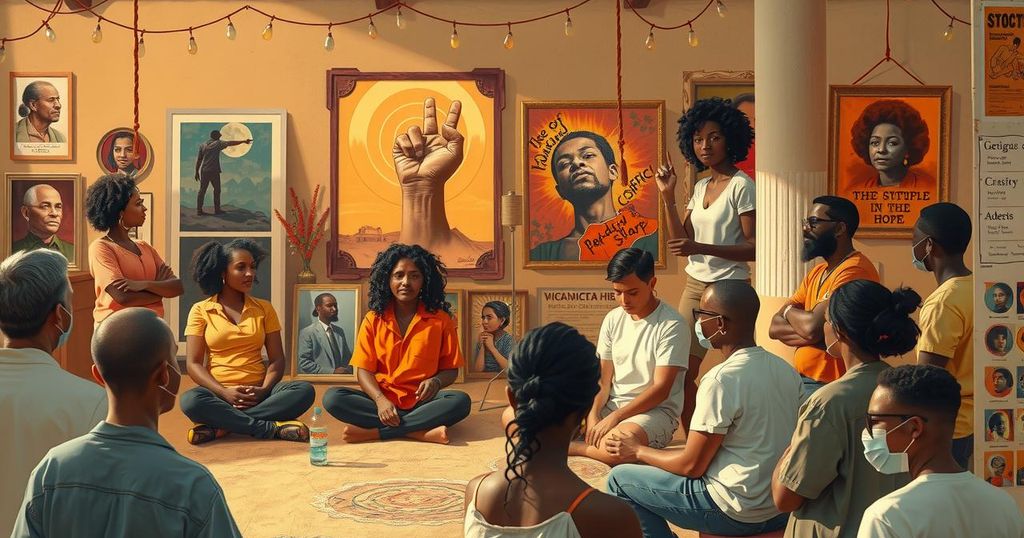

On Monday at the Elliott School of International Affairs, Chilean human rights activists Veronica De Negri and Marco Echeverría engaged in a dialogue about the collective trauma stemming from Augusto Pinochet’s regime. The event was facilitated by LATAM@GW, a student organization dedicated to discussing issues pertinent to Latin America and the Caribbean, and moderated by Rosela Millones, a researcher specializing in collective memory from the University of Chile.

De Negri and Echeverría emphasized the vital role of commemorating the victims of the Pinochet regime and addressing Chile’s painful history. Pinochet’s coup d’état on September 11, 1973, which was aided by U.S. covert operations, marked the beginning of 17 years of severe oppression, where thousands of dissenters and innocent civilians were subjected to torture, kidnapping, and murder by the regime.

De Negri asserted, “What I can tell you is this thing happened. Not as an accident, these things happen by political decision, be very clear about that, always have the government involved.” Millones elaborated on the profound and enduring impact of the regime’s violence on contemporary Chilean society, stressing that many human rights violations remain unresolved, with thousands of individuals still unaccounted for due to societal reluctance to confront this past.

Following Pinochet’s exit in 1989 and the new presidency that began in 1990, there has been a significant delay in research and acknowledgment of the psychological scars left by the regime. Millones mentioned that 2023 marks the initiation of a nationwide research effort aiming to locate over 1,000 individuals still missing and recognized the ongoing anguish stemming from these unhealed wounds.

De Negri shared a personal tragedy, recounting the brutal death of her son, Rodrigo, who was arrested and subsequently burned alive during an anti-Pinochet protest in 1986. She expressed the struggle against forgetting these traumatic events, observing that a colleague, who had also faced arrest, now chooses to deny the painful memories associated with the regime.

Echeverría recalled his own experience as a student activist, noting he was subpoenaed three times during pursuits for democracy. He commented that the post-Pinochet government preferred to overlook this dark chapter of history, prioritizing a progressive outlook over remembrance. “With the new wave of democracy in Chile, there was a big effort to not remember, to keep moving forward, to not dwell on the past,” he stated.

To enable public engagement with the past, Echeverría argued for the establishment of memorials and educational sites that foster understanding and remembrance of the regime’s atrocities. De Negri poignantly remarked on the importance of memory, emphasizing the collective responsibility to never forget the past to prevent its recurrence. “Memory is something that we cannot forget because we have a responsibility in this world,” she reiterated, underscoring the consequences of societal amnesia.

The discussions held by Chilean activists reflect a critical examination of the impact of Pinochet’s regime on collective memory and societal healing. Emphasizing the importance of remembrance, the speakers advocate for research and memorialization to honor the victims and ensure that such atrocities are not repeated. The ongoing struggle against forgetting serves as a reminder of the responsibilities that come with historical acknowledgment and the need for a proactive approach to uphold human rights.

Original Source: gwhatchet.com