The dominance of English in scientific publications creates significant barriers to global climate literacy, restricting access to vital climate change information for the majority of the world’s population who do not speak the language. This linguistic inequality exacerbates existing disparities in knowledge production and social justice, particularly affecting developing countries. Initiatives such as UNESCO’s Open Science and Climate Cardinals aim to bridge these gaps by promoting multilingualism and making climate information accessible to non-English speakers.

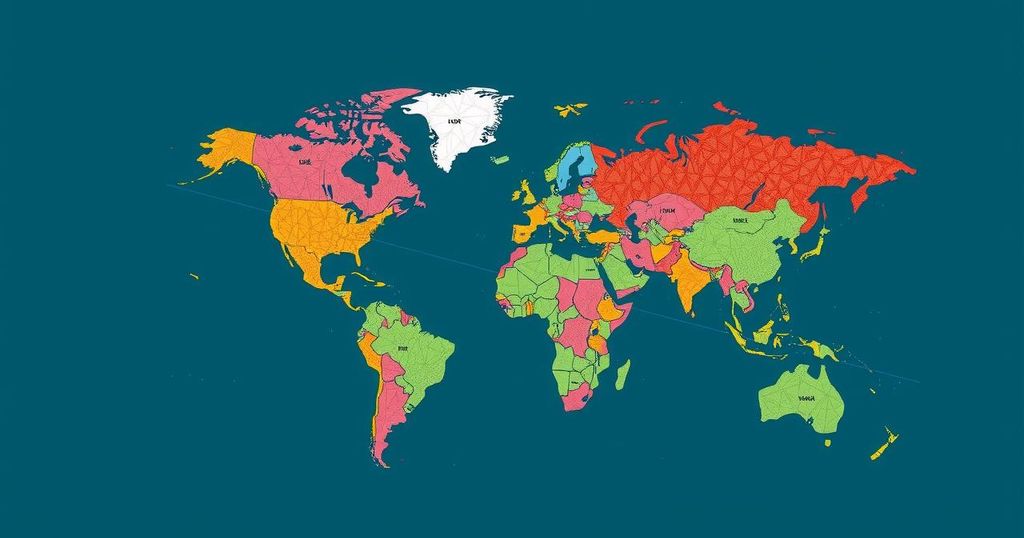

The increasing severity of climate change presents an urgent global challenge that impacts every individual on the planet. It is indeed logical for scientific literature concerning global warming to be predominantly published in English, a language deemed as the global lingua franca. However, this English-only approach paradoxically renders climate science largely inaccessible to the majority of the global population. To illuminate this discrepancy, it is necessary to examine relevant statistics: approximately 90% of scientific publications are in English, reflecting its overwhelming dominance as a scientific medium. Despite being termed a global language, English is spoken by only a minority. In fact, the countries where English is the primary language, such as the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, collectively account for about 400 million speakers, a mere fraction of the global populace. In various former British colonies, English exists alongside numerous indigenous languages, positioning it as an elite medium primarily utilized by a select urban, educated demographic. This situation further complicates the determination of accurate English speaker statistics; indeed, estimates suggest that between 1 and 2 billion may speak English, with even the higher estimate only comprising one-quarter of the global population. Consequently, approximately 75% of the world lacks proficiency in the language through which crucial climate change science is communicated. This linguistic disparity significantly hampers equitable access to scientific knowledge regarding climate change and exacerbates existing inequalities. Scientific output continues to be concentrated in Anglophone nations, namely the US and the UK, which contribute substantially to the most prestigious scientific journals. The lack of accessibility to English literary works particularly disadvantages developing countries, whose populations are disproportionately affected by climate change yet are often deprived of necessary scientific literature. To address these challenges, UNESCO’s Open Science initiative strives to democratize scientific research access across languages, aiming to remove geographic and linguistic barriers that hinder collaboration. Promoting multilingualism within scientific discourse and utilizing advancements in machine translation technology, particularly through the efforts of organizations like Climate Cardinals, are concrete steps towards creating an inclusive climate movement. Their mission is to provide translated climate information in over 100 languages, effectively bridging the gap between scientific research and non-English speakers. Such initiatives not only enhance climate literacy but also catalyze effective action against climate change, offering a pathway towards a more equitable and informed global community.

As the urgency of climate change escalates globally, effective communication of scientific research has become imperative. However, there exists a significant language barrier, as the overwhelming majority of scientific literature is published in English. This reality restricts access to vital information specifically for populations who do not speak the language, primarily affecting individuals in developing countries who are facing the most severe consequences of climate change. The notable lack of representation of indigenous languages within scientific communication establishes a critical communication gap that hinders global climate literacy and awareness, necessitating an urgent reevaluation of how climate science is disseminated.

In summary, the dominance of English in scientific discourse underscores a linguistic inequality that not only limits climate literacy but also perpetuates wider social injustices. The fact that a substantial portion of the global population lacks access to climate science exacerbates vulnerabilities in regions most impacted by climate change. Initiatives like UNESCO’s Open Science and the efforts of Climate Cardinals represent essential steps toward dismantling these barriers and fostering a more inclusive and informed dialogue on climate issues, ultimately empowering diverse communities to participate in climate action.

Original Source: theconversation.com